GC-MS

How Did Syrian Bitumen End Up in Anglo Saxon Graves? — Chromatography Investigates

Dec 16 2016

One of the most famous and important archaeological sites in the UK is Sutton Hoo in East Anglia. Sutton Hoo is the site of two cemeteries dating from the sixth and seventh centuries and has delivered a wealth of artefacts to archaeologists since major excavations took place in 1939.

One of the main finds was a complete ship burial — but as a recent paper in PLOS One shows — Identification, Geochemical Characterisation and Significance of Bitumen among the Grave Goods of the 7th Century Mound 1 Ship-Burial at Sutton Hoo (Suffolk, UK) — the site is still delivering exciting finds today.

Anglo Saxon graves

Sites like Sutton Hoo give archaeologists and historians an insight into how settlers in the UK lived almost 1,500 years ago. Very few written records exist from the period — artefacts, family dwellings and funeral sites offer researchers a window into their world.

The first major examination of the Sutton Hoo site was in 1939 — although previous excavation in medieval times and in the sixteenth century took place — and it was during these excavations that the main finds which made Sutton Hoo famous were found. Ship’s rivets still in place after fifteen hundred years revealed a major find — a complete ship’s hull with a burial chamber.

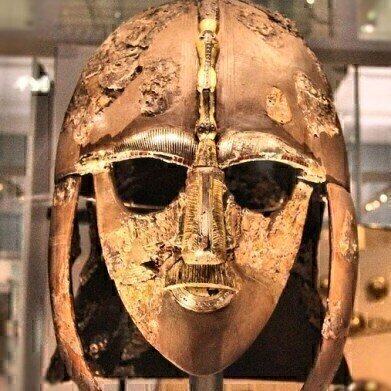

It is thought that the ship and burial chamber belong to Rædwald who was a 7th-century king of East Anglia. One of the most magnificent finds was an Anglo-Saxon helmet thought to belong to the king. Not too much is known about the king due to the lack of records — they were destroyed when the Vikings invaded in the ninth century and destroyed the local monasteries.

Treasure comes in all colours — including black

But amongst the helmets, shields, gold and jewels were modest finds that were catalogued and stored in the British Museum. One of the modest finds were lumps of black ‘rocks’ — which no one could identify until chromatography looked deep into the past.

A team of researchers from the British Museum and the University of Aberdeen have used modern analytical techniques in re-examining the black lumps. Alongside reflectance transformation imaging and infra-red spectroscopy — the team used gas chromatography in tandem with mass spectrometry. The use of GC-MS is discussed in the article, Adding more Power to your GC-MS Analysis through Deconvolution.

Syrian tar in East Anglia?

The researchers found that the lumps were bitumen. One use of bitumen was in waterproofing boats — but it had many other uses in the ancient world including embalming and medicine. But the team knew that the people of East Anglia did not trade with the rest of England at the time. So where did the bitumen come from.?

Comparing the samples with reference samples revealed to the team that the most likely origin of the bitumen was from Syria. As to what the Anglo-Saxons were using the bitumen for — well, the researchers don’t know. Another question for another day.

Digital Edition

Chromatography Today - Buyers' Guide 2022

October 2023

In This Edition Modern & Practical Applications - Accelerating ADC Development with Mass Spectrometry - Implementing High-Resolution Ion Mobility into Peptide Mapping Workflows Chromatogr...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 20 2025 Amsterdam, Netherlands

Feb 03 2025 Dubai, UAE

Feb 05 2025 Guangzhou, China

Mar 01 2025 Boston, MA, USA

Mar 04 2025 Berlin, Germany